PDF: Hartley_Cliburn-review_June-21-2022-e

Review of Yunchan Lim’s Gold Medal winning performance at the 16th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition

Sergey Rachmaninoff, Piano Concerto No. 3 in D-minor

Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Marin Alsop

June 19, 2022 (performance) | June 21, 2022 (review published)

Kris Hartley

Overview

That Yunchan Lim’s performance of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 3 (link) won him Gold Medal at the 16th Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Fort Worth, Texas is not the biggest story of this moment. Indeed, Cliburn Competition medalists are forever associated with their accomplishment in one of the world’s top piano competitions; the honor often appears among the first lines of bios in concert programs, even for veteran pianists. In Lim’s case, however, this performance did not merely win him a prize but announced his artistry to the musical world in an early milestone among what will surely be many. The Cliburn Foundation treats all of its winners as lifelong family, and Lim – like medalists before him – will always possess Fort Worth’s proverbial ‘key to the city’ even as he is thrust immediately into the global musical spotlight.

The performance won Lim not only this Cliburn Competition but, in my view, the past 20 years of competitions. I was a volunteer with former backstage mother Louise Canafax and current backstage mother Kathie Cummins at the 11th Competition in 2001, seeing Olga Kern and Stanislav Ioudenitch share the Gold Medal. I recall being in the audience for Kern’s astonishing performance of the Rachmaninoff Third – at the first Cliburn Competition held at Bass Hall – and sensed, as did everyone, that she was an artist for the ages. In the same role in 2005, I witnessed Alexander Kobrin’s thrilling victory and later saw him perform with the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra. As a kid, I saw the late Alexei Sultanov’s post-Gold tour at his recital stop in Lexington, Kentucky (around 1990). In this regard, I have some personal experience with the history of the Cliburn Competition that, in a small way, makes up for my amateur status as a musical reviewer.

Regarding the performance itself, Lim carries forward a tradition of Gold Medalists playing the Rachmaninoff Third, as did fellow South Korean Yekwon Sunwoo at the 15th Cliburn Competition in 2017. Lim did as much to speak with his own voice as he did to acknowledge the rich history of performances of this monumental concerto, something I am probably not the only person to appreciate. Throughout my brief but failed dip into the musical world as a career, I grew weary of the incessant refrain that musicians always need to “say something new” in performing a piece of music. I am now in a profession – academic research – that asks the same from any new publication. I sometimes wonder why it is not enough for a pianist to deliver a thoughtful, personal, and sincere performance without needing to sound like nobody ever has before. This is an unreasonable expectation.

With that said, Lim brought both novelty and history to his playing. I believe that a consummate artist appreciates the greatness that came before. To be sure, most pianists have their historical favorites and acknowledge as much in interviews and casual conversations. However, it takes a special artist to make a personal imprint on a piece while, through the performance itself, bringing listeners into the world of the past. What I am getting at is this: I heard more Horowitz (New York Philharmonic/Ormandy, 1978) in Lim’s playing than in any performance of the Rachmaninoff Third I have ever heard, live or recorded (by my estimation about 2,000 listens, many repeated of course). This is what motivated me to write this review. Lim’s performance was no facsimile; rather, he found a brilliant balance between expressing his individuality and honoring the past in subtle and creative ways.

First movement

Resisting the urge to immediately reveal the depth of his technical prowess even against the mood of the music, which a competition can trick some pianists into doing, Lim presented an unpretentious but lyrical walk through Rachmaninoff’s understated opening passages (until 3:24). Where most pianists come crashing past the first solo run before the Moderato, Lim pulls back as if to say “let’s not get ahead of ourselves.” He moves on to deliver the supple a tempo espressivo theme without the drippy sentimentality that tempts many pianists, but at the same time lets the phrasing breathe in a way that provides an effective foil for the tempest to come (4:43-5:00). His brief pause right at the end of the allargando and before the a tempo (5:57) was the first moment when I began to sense something special at hand – it was beautifully in-sync with conductor Marin Alsop and the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra. As broadcast commentator Buddy Bray said before Lim walked onto the stage, the Rachmaninoff Third is a study in concentration. To that descriptor, I would add discipline. For example, Lim has the technique to rip through the high notes right before Rehearsal Mark 10 (6:41-6:46), but instead takes them as an opportunity to reflect – each a little softer than the previous. He thus shows himself early on to be patient and mature beyond his years. By the time Lim gave a sensual reading of tempo precedente, ma un poco piu mosso – where he and the orchestra remained tightly coordinated (6:51-7:18) – this performance was already presenting itself as pure musicmaking rather than a chase to the medal. His return to Tempo I (7:29) kept me at the edge of my seat and his piu vivo (8:36) propelled forward convincingly. The climax of this passage – eight ascending A-minor cords played simultaneously by piano and orchestra (9:24) – can deteriorate into a clumsy mess in the hands of hurried or less capable musicians. There is little more heart-breaking than executing the lead-up and not sticking the landing. Lim and Alsop pulled it off and the excitement remained unbroken. I was still with them as a listener, eager for more and relieved not to be thinking of excuses.

We come to expect the extended version of the first movement cadenza when hearing the Rachmaninoff Third concerto, particularly at competitions – where pianists often mistakenly believe that they need every opportunity to flex their muscles. In a mild surprise, Lim resisted this lure and opted for the short cadenza (like Argerich and Horowitz; 11:10). Compared to its meaty, chord-ey bigger sibling, this snappy cadenza provides a greater variety of musical moments (from playful to contemplative to majestic) and it was fleet and clean in Lim’s nimble hands. His back-and-forth chords (11:42) were clear and even, which is about all you can ask at this level of technical difficulty. Lim’s passion at the climax of the cadenza (12:19) was matched in several other moments of the concerto – and I reckon once again that this reflects the maturity of his approach; it is taxing on an audience, and unconvincing to boot, to hear a pianist at peak-passion for an entire 45 minutes. This is not to say that Lim slepwalked at all. Cute little delights hide out in his performance for those who are paying close enough attention – an example is his portato (from my theory class, as I recall, a measured and separated touch somewhere between staccato and legato) in the descending left-hand notes before Come prima (14:20) – again, something I have not heard in other recordings. Taking the cadenza’s final trill between two hands (15:01) was a nice touch that allowed Lim some extra gravity in the weighty moments before the movement’s hushed close.

Second movement

Lim’s swirly, mysterious entrance in the second movement foreshadowed the white-hot passion to come (20:12). The movement unfolds like a plot build-up, each flurry and passage more urgent than the last. Lim understood and relished this structure, holding back before launching headlong into a piu vivo (22:45) reminiscent of Martha Argerich (Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin/Chailly, 1982), again with ominous runs in the left hand that set the mood for the even darker transition to a tempo piu mosso. Lim’s next nod to Horowitz’s towering, godlike performance came in the low B-flat that introduces the recapitulation of the theme in a tempo piu mosso (23:47). How did Lim make the Bass Hall piano sound, at that exact moment, like Horowitz’s famous personal piano (New York Philharmonic/Mehta, 1978)? I believe Lim added an extra note, but it must be more – something special in his touch. It was an incredible moment and by this point in the performance he was clearly distinguishing himself. Further, his handling of the left-hand ascending chords right before Rehearsal Mark 29 (24:14) was masterful; I have played (around with) this piece myself and know how difficult it is to sync those chords with what is happening in the right hand. His pulsing sense of rhythm helped him – and all of us listening – make sense of it.

Now comes the heart of my review. I did not actually yell “Horowitz” out loud (in my Budapest hotel room in the middle of the night, as the concert was broadcast live on YouTube) until Lim struck the low A (24:20) before the great D-major outburst. This was my favorite single note of his entire performance, and probably of the entire competition. Lim flips down the keyboard in an instant with his right hand in a kind of lightning strike, eliciting once again a very Horowitzian sound that remains such a beautiful mystery – both pianists completely immersed in the musical moment while totally comfortable and confident. Lim’s complete passion was finally breaking through at exactly the right moment. Like many things in life, the note itself has little meaning without its context, and the way Lim pulled off the passage that the low A introduces brought the whole narrative together as few pianists can. He executed the stately and hair-raising D-major (24:22) and D-flat major (24:44) passages with every bit of the gravity Rachmaninoff needs in that delicious moment – breaking the shackles and sinking his teeth into the meaty, luscious chords (again, the low registers in the D-flat passage sound miraculously like the Horowitz recordings. How does Lim do it?).

From then and for the next half hour of Lim’s performance, I knew I was witnessing history. This is the divine beauty of such a performance: its historic gravity does not – cannot – announce itself immediately but reveals itself incrementally. When the listener arrives at the realization of something so special, the remainder of the experience is pure ecstasy. My only critique for the orchestral accompaniment is that the strings should have better fluffed the bed throughout the D-major passage. For a yearning, heart-on-sleeve example, refer to Leonard Slatkin’s recording with pianist Abbey Simon and the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra (a recording I grew up with).

Third movement

From the mid-point of the second movement onwards, Lim’s performance was essentially a coronation march. I have the image of him in sunglasses being carried in a sedan chair, pointing to and smiling at admirers in the passing crowd. He launches into L’istesso tempo, the frenzied lead-in to the third movement (28:29), with a white-hot intensity requiring technique few pianists possess. I am reminded here, again, of Argerich but also of lesser known recordings by the inimitable Grigory Sokolov – particularly the descending motif (Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra/Ollila, 1998). Throughout the final movement, Lim’s overarching vision is clear while going long on detail. For example, he picks up so well the left-hand leaps (29:48) in the movement’s second theme in A-minor (repeated later in E-flat-major), which are essential for maintaining the counterpoint that defines these passages. The climax moment (31:05) of the third theme is masterfully executed, as Lim enjoys total harmony with the orchestra. He makes the beginning of the center section (32:02) – molto leggiero – sound more like allegro but that is a matter of taste; I would have preferred a little more breathing in these earlier passages, but he was on a roll and who was to stop him? Lim does, however, take some time to reflect in the meno mosso (33:41; for a masterclass in that passage’s counterpoint wonders, to say nothing of velvety tone, refer again to Argerich; both Lim and Argerich effectively bring out the passage’s momentum in the later stages).

Lim’s execution of the lento section again displayed a musical maturity beyond his years – note, for example, how he takes personal responsibility for cueing the flute solo (35:22) in a moment that makes me want to see him accompany the Francis Poulenc Flute Sonata. The key change immediately after the solo (35:32) drips with the smooth luxury of melted butter, in both tone and phrasing; simply gorgeous in a brief but not indulgent pause. In this moment, I sense the pianist-as-sculptor, shaping the phrase in a way I can see as much as hear. One of the big stories of Lim’s third movement is also the contrast between two virtuosic passages of four repeated phrases, the first starting in C-major (30:11) and second in B-flat-major (38:50). How the earlier one is played typically provides a hint into the style of the second, but in this instance, Lim teases the audience as the second takes us on a galloping ride few could imitate. More on this in a moment.

We arrive now at the concerto’s coda, and Lim’s performance is stretching me for new words. He takes off at piu vivo (37:49) like Argerich at an Old West piano duel, but never seems to play beyond himself (something a pianist with only his capacity can pull off). By now, the audience may be starting to think that this will be another of history’s many rousing and hasty conclusions to Rachmaninoff’s grand concerto, which would have been perfectly suitable for earning the Gold. However, we know not what is in store until Lim launches into something superhuman at the aforementioned B-flat-major passage (38:50). I estimate that I have probably listened to a hundred different performances of this concerto on LP, cassette tape, CD, and in person (including many at the Cliburn Competition). I have never heard the passage played like this. Was it a display of virtuosity? Of course! But Lim earned this indulgence because he had already proven his musical versatility – both sensitive and powerful. This was purely a matter of “I can, therefore I will.” He pulled it off with tremendous effect; aim for the king, and you better not miss.

On a technical note, this is a particularly difficult passage and many pianists cheat by picking up only the octaves in the right hand. In fact, those are not octaves but chords, and the full effect cannot be appreciated without the inner workings of those chords – which highlight a descending chromatic scale for a brilliant counterpoint. To clearly express this at any speed is remarkable. When slower, perhaps it can be better appreciated (refer to Abbey Simon). For Lim, it was so fast that the only way I could detect the inner chords was, simply, to watch the video and see if the keys were pressed. It appears that he does not cut corners here – major kudos for that. Again, I think this is another nod to Horowitz (who goes absolutely crazy on these chords, not in speed but in muscle, and picks up the counterpoint if without much subtlety). For listeners who really know the score, on the fourth repeat of that figure (in D-minor), Lim caught the left-hand B-natural octave as he was rounding the corner to F-major (39:16). This often-ignored note is actually a crucial turning point in the passage, signaling a satisfying redemption in the move from darkness to light. It is one of those types of details that distinguish Rachmaninoff as a compositional master. I cannot underscore how rare the proper execution of this note is. The best I have heard at this blistering speed is Yefim Bronfman (Vienna Philharmonic/Gergiev).

The final cornerstone moment I listen for in performances of the Rachmaninoff Third is how pianists handle the repeated left-hand octaves in the vivace “march” (40:15). Astute listeners will note that the chord progressions are the same as those in the first movement cadenza, giving the piece an element of cohesion. I expected Lim to pull these off with the ease of Sunday morning, and he did exactly that. It may be a shallow criterion, but I view this passage as a pianist’s opportunity to exhibit the technical chops to handle whatever Rachmaninoff assigns. Surprisingly, many otherwise wonderful professional pianists just blast through this passage, stabbing at the notes and hoping for the best (and hoping that we will neither notice nor care). Others, like Lim, take a more calculated approach; the best example I have heard is Lazar Berman’s gorgeously balanced if mechanical reading (London Symphony Orchestra/Abbado). We should not dwell unduly on raw virtuosity, particularly when musicality and lyricism win hearts (and sometimes competitions), but it cannot be ignored either. From this point forward, Lim had the whole Bass Hall crowd and probably the piano world in the palm of his hand. At the build-up and climax of the entire concerto (41:44), I doubt there were many dry eyes left. It was history unfolding. Many have noted that Alsop wiped away a tear as the piece concluded. I must say that she held it together better than I did!

In closing

As is the case for many piano fans, my favorite performances of the Rachmaninoff Third are those I grew up with: Lazar Berman, Van Cliburn, Byron Janis, Martha Argerich, and, of course, Vladimir Horowitz. The astute listener can probably understand, based on my preferences, why I appreciated Lim so much. His sound and aura are stately and unfussed. I am not on the inside of the piano world, but my sense is that some in the new generation of pianists can be a bit on the cautious side – not wanting to overstep, overindulge, make it about themselves, or be seen as garish and tasteless. Lim is none of these things but also does not appear unduly preoccupied with avoiding them; he delivers a heart-on-sleeve performance while his technique keeps it virtually note-perfect. As the enthusiastic and thoughtful Buddy Bray said at the conclusion, the performance was nothing short of miraculous. Like most people, I did not need to hear from anyone else how well Lim did – we all knew immediately from the performance itself. The roar of the crowd told the tale. Fort Worth audiences are always enthusiastic, but this explosion of rapturous applause was rare in my view – not since Olga Kern in 2001 and the Alexei Sultanov in 1989 was there something similar.

Alsop had the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra sounding at the top of its game for this performance – lush strings for the most part and woodwind delicacy that often gets obscured amidst what is a rather busy orchestration (see also the woodwind solos in the first movement cadenza, which were a particular delight). There is so much more to say about every note of this performance, but for brevity I have focused here on the big ideas. Lim’s effort will certainly reward years of repeated listenings and was a musical experience for the ages. I look forward to being moved by him for decades to come.

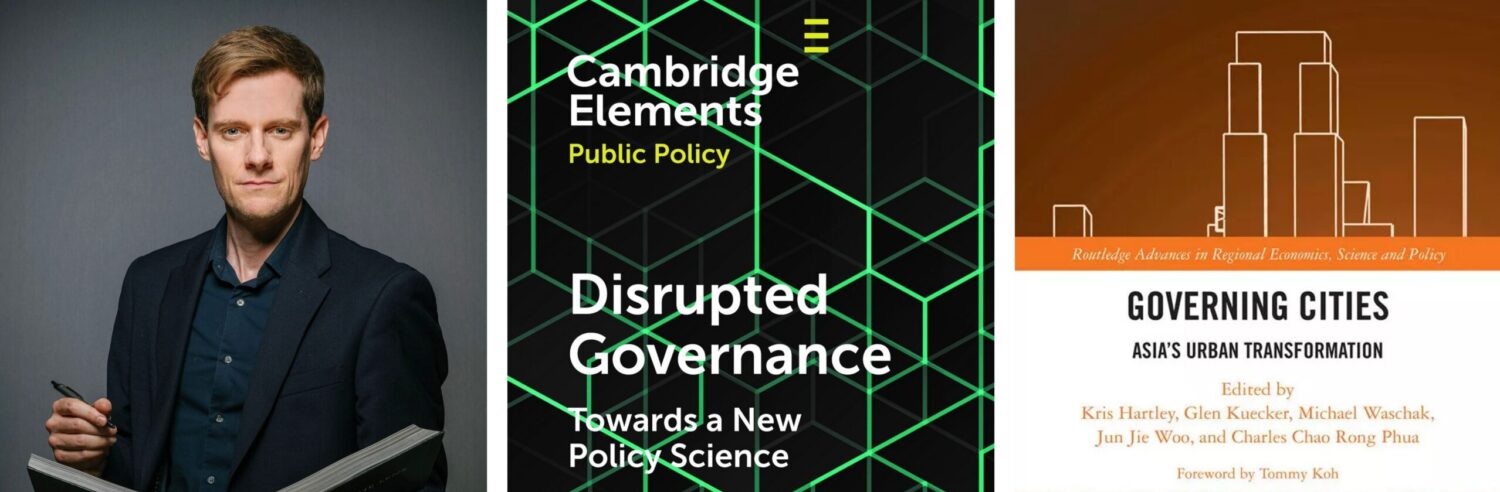

Kris Hartley is an incoming Assistant Professor of Public Policy in the Department of Asian and International Studies at City University of Hong Kong. His research addresses global-to-local policy transfer in the application of technology to sustainability transitions. He volunteered backstage at the 2001 and 2005 Van Cliburn International Piano Competitions and at the 2002 Van Cliburn International Amateur Competition. Though a Classics major in college, he studied piano under David Northington at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He began his piano studies with Roland Schneller and Craig Nies at the pre-college program in the Blair School of Music at Vanderbilt University. Kris is originally from Nashville and is a failed pianist but passionate listener.